CORPORATE ACTION

Will Refills Be A Disruptive Format?

Refills are having a moment.

We recently undertook some research on the refill market and see a proliferation of ideas. And notably, they could go a long way to solving the CPG’s plastics crisis.

Large-scale uptake of refills would allow CPG companies to deliver product to consumers with a greatly reduced plastic footprint, and save substantially more plastic than sticking with current formats, even if they meet their recycled-content targets.

But refills have had a rocky road. At different points since at least the 1970s they’ve been promoted for being less environmentally damaging but have never really taken hold.

A 2008 report by Wrap, the UK’s Waste and Resources Action Programme, a charitable organization, reviewed different ways refilling could abate plastic use for food and non-food products. It looked at existing systems in use in the USA, Australia, New Zealand, mainland Europe and the UK and found a series of promising models, the best two being:

A 2011 article looked at the dismal performance of refills in the UK. Despite offering discounts of up to 67% (but an average about 26%) consumer uptake was low. For example, in 2002 The Body Shop stopped offering a shampoo refill service because just 1% of customers used it. Ecover, which offered refill stations at 600 health-food stores, acknowledged it was “unfeasible” to offer them in supermarkets, pointing to the infeasibility of the store space needed and mess created by consumers.

But things are changing.

In August, Waitrose extended Unpacked, its initiative to reduce packing because, according to Tor Harris, head of corporate social responsibility for Waitrose, consumer reaction to the trial had been "incredible."

Unpacked lets consumers fill their own containers with a range of products. Beyond common offerings like dried foods, there are also frozen foods, fresh food prepared by a chef, flowers, beer and wine, and detergent and dishwashing liquid, for which it partnered with Ecover. Clearly, Ecover which is now owned by SC Johnson, has changed its tune on the potential of supermarket refilling and is actively promoting refilling with its “Refillution” theme

Meanwhile, Boots is partnering with eco beauty brand Beauty Kitchen to enable consumers to refill their empties. Since August, Boots has provided Beauty Kitchen refill stations at its flagship store in Covent Garden, London.

Meanwhile, Boots is partnering with eco beauty brand Beauty Kitchen to enable consumers to refill their empties. Since August, Boots has provided Beauty Kitchen refill stations at its flagship store in Covent Garden, London.

Beauty Kitchen founder, Jo Chidley, said: “We’re the first beauty brand in the world to set up something like Return · Refill · Repeat, but it’s not a new idea - we’ve simply taken inspiration from the milkman, then applied it to beauty.”

Some major brands are also looking at refills. Earlier in the year we mentioned that P&G’s Olay will be testing a refill approach to reducing single-use plastic. In October, shoppers will be able to buy a refillable Olay Regenerist Whip moisturizer that will include a full jar and a refill pod, to be inserted in the empty jar. It will be sold and shipped in a 100% recycled paper container with no outer carton. The pods are made from recyclable polypropylene. It will be trialed on Olay.com in the US and UK, as well as selected online retailers, for three months, and in time, the brand may sell the pods separately.

So what’s changed? Consumer opinion, mostly. Concern about plastics and the environment is translating into a willingness to shop differently, which is building demand for refills. One wild card here that could tip the scales in favor of refill models is a possible plastics tax. Consumers are very sensitive to taxes that push them in a direction they know is ‘right.’ Plastic bag usage in the UK, for example, fell 86% on the back of a 5p charge on plastic bags (likely less than 0.25% of a typical bag-requiring purchase). A material plastic tax could grease the skids for refills.

However, refill stations run into serious limitations. They require the consumer to do the work, take up valuable retail space and choice is limited. Consumers today want their granular variants and that’s not possible with refill stations.

A marketplace ready for disruption?

But beyond consumer concern, today’s marketplace is different in other significant ways since Wrap looked at promising solutions.

One change is the growing feasibility of sending liquid refills in the mail. These pouches are mostly single-use plastics but some vendors are now offering to reuse them. And it won’t be long before they are compostable. Add in powder or high-concentrate solutions (dilute at home) and this looks a promising option.

One major benefit of mailed refills is that it will let consumers have the choice they are now accustomed to.

Another key difference is today’s distribution system, which is so much richer. Amazon and others have educated us to shop online and we’re used to the choice and convenience it brings.

Loop, in pilot since the spring, is leveraging UPS in its refill model. It’s backed by most of largest CPG companies, but the containers are large and costly and consumers may prefer the choice available through mailed refills.

As part of our research, we looked at vendors pushing this mailed-refill model. There are a number of small and often new players. Splosh (not so new, since it started in 2012) is a small UK-based online retailer that is committed to reducing plastic waste: "Splosh is different – because every bottle we sell is refillable with concentrates you cut plastic waste by 90%. By returning used refill pouches to us, we can virtually eliminate plastic waste".

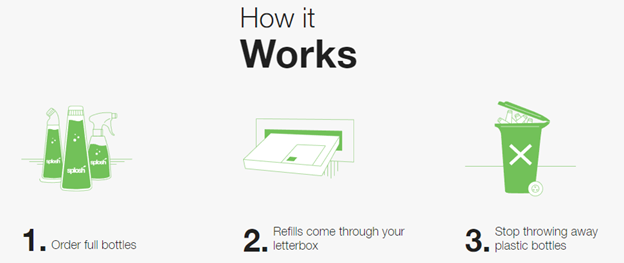

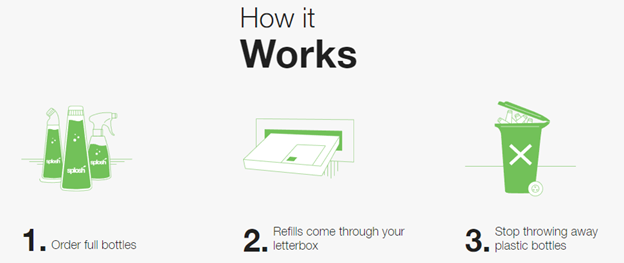

On its website, Splosh makes it clear how it works:

Splosh offers a range of home, kitchen and personal care products. Refill packs are the same volume and price as the original plastic bottle but come with free delivery for an effective delivered cost of 1.3p/ml.

Larger brands offer sizable discounts for refills. For example, unit costs of refills for Method hand wash are 44% of the bottle unit cost. Refills for L'Occitane shampoo is 56%. These are delivered cost for sachets. They aren’t compostable or reused, but that may change. But either way, the price proposition looks compelling.

Mailed refills look to be a promising and scalable solution that would allow CPGs to deliver product with a greatly reduced plastic footprint, and give consumers some convenience, preserve their choices and lower costs.

Contact us if you want to know more.[Image Credit: © Beauty Kitchen]

We recently undertook some research on the refill market and see a proliferation of ideas. And notably, they could go a long way to solving the CPG’s plastics crisis.

Large-scale uptake of refills would allow CPG companies to deliver product to consumers with a greatly reduced plastic footprint, and save substantially more plastic than sticking with current formats, even if they meet their recycled-content targets.

But refills have had a rocky road. At different points since at least the 1970s they’ve been promoted for being less environmentally damaging but have never really taken hold.

A 2008 report by Wrap, the UK’s Waste and Resources Action Programme, a charitable organization, reviewed different ways refilling could abate plastic use for food and non-food products. It looked at existing systems in use in the USA, Australia, New Zealand, mainland Europe and the UK and found a series of promising models, the best two being:

using a glass jar as the primary pack with a flow-wrap or pouch refill (examples were seen for coffee and jam in overseas markets); and

a primary pack with a pump dispenser where the refill had a screw cap instead of a pump (many examples were seen, mainly for soaps and hair care products).

A 2011 article looked at the dismal performance of refills in the UK. Despite offering discounts of up to 67% (but an average about 26%) consumer uptake was low. For example, in 2002 The Body Shop stopped offering a shampoo refill service because just 1% of customers used it. Ecover, which offered refill stations at 600 health-food stores, acknowledged it was “unfeasible” to offer them in supermarkets, pointing to the infeasibility of the store space needed and mess created by consumers.

But things are changing.

In August, Waitrose extended Unpacked, its initiative to reduce packing because, according to Tor Harris, head of corporate social responsibility for Waitrose, consumer reaction to the trial had been "incredible."

Unpacked lets consumers fill their own containers with a range of products. Beyond common offerings like dried foods, there are also frozen foods, fresh food prepared by a chef, flowers, beer and wine, and detergent and dishwashing liquid, for which it partnered with Ecover. Clearly, Ecover which is now owned by SC Johnson, has changed its tune on the potential of supermarket refilling and is actively promoting refilling with its “Refillution” theme

Meanwhile, Boots is partnering with eco beauty brand Beauty Kitchen to enable consumers to refill their empties. Since August, Boots has provided Beauty Kitchen refill stations at its flagship store in Covent Garden, London.

Meanwhile, Boots is partnering with eco beauty brand Beauty Kitchen to enable consumers to refill their empties. Since August, Boots has provided Beauty Kitchen refill stations at its flagship store in Covent Garden, London.Beauty Kitchen founder, Jo Chidley, said: “We’re the first beauty brand in the world to set up something like Return · Refill · Repeat, but it’s not a new idea - we’ve simply taken inspiration from the milkman, then applied it to beauty.”

Some major brands are also looking at refills. Earlier in the year we mentioned that P&G’s Olay will be testing a refill approach to reducing single-use plastic. In October, shoppers will be able to buy a refillable Olay Regenerist Whip moisturizer that will include a full jar and a refill pod, to be inserted in the empty jar. It will be sold and shipped in a 100% recycled paper container with no outer carton. The pods are made from recyclable polypropylene. It will be trialed on Olay.com in the US and UK, as well as selected online retailers, for three months, and in time, the brand may sell the pods separately.

So what’s changed? Consumer opinion, mostly. Concern about plastics and the environment is translating into a willingness to shop differently, which is building demand for refills. One wild card here that could tip the scales in favor of refill models is a possible plastics tax. Consumers are very sensitive to taxes that push them in a direction they know is ‘right.’ Plastic bag usage in the UK, for example, fell 86% on the back of a 5p charge on plastic bags (likely less than 0.25% of a typical bag-requiring purchase). A material plastic tax could grease the skids for refills.

However, refill stations run into serious limitations. They require the consumer to do the work, take up valuable retail space and choice is limited. Consumers today want their granular variants and that’s not possible with refill stations.

A marketplace ready for disruption?

But beyond consumer concern, today’s marketplace is different in other significant ways since Wrap looked at promising solutions.

One change is the growing feasibility of sending liquid refills in the mail. These pouches are mostly single-use plastics but some vendors are now offering to reuse them. And it won’t be long before they are compostable. Add in powder or high-concentrate solutions (dilute at home) and this looks a promising option.

One major benefit of mailed refills is that it will let consumers have the choice they are now accustomed to.

Another key difference is today’s distribution system, which is so much richer. Amazon and others have educated us to shop online and we’re used to the choice and convenience it brings.

Loop, in pilot since the spring, is leveraging UPS in its refill model. It’s backed by most of largest CPG companies, but the containers are large and costly and consumers may prefer the choice available through mailed refills.

As part of our research, we looked at vendors pushing this mailed-refill model. There are a number of small and often new players. Splosh (not so new, since it started in 2012) is a small UK-based online retailer that is committed to reducing plastic waste: "Splosh is different – because every bottle we sell is refillable with concentrates you cut plastic waste by 90%. By returning used refill pouches to us, we can virtually eliminate plastic waste".

On its website, Splosh makes it clear how it works:

Splosh offers a range of home, kitchen and personal care products. Refill packs are the same volume and price as the original plastic bottle but come with free delivery for an effective delivered cost of 1.3p/ml.

Larger brands offer sizable discounts for refills. For example, unit costs of refills for Method hand wash are 44% of the bottle unit cost. Refills for L'Occitane shampoo is 56%. These are delivered cost for sachets. They aren’t compostable or reused, but that may change. But either way, the price proposition looks compelling.

Mailed refills look to be a promising and scalable solution that would allow CPGs to deliver product with a greatly reduced plastic footprint, and give consumers some convenience, preserve their choices and lower costs.

Contact us if you want to know more.[Image Credit: © Beauty Kitchen]

CORPORATE ACTION: Coca-Cola

DASANI Announces Series Of Plastic Reduction Initiatives

DASANI’s owner, The Coca-Cola Company, has pledged to make its bottles and cans with an average of 50% recycled material by 2030. In support of this goal, DASANI announced a “robust pipeline” of efforts to lower its plastic footprint. Its HybridBottle, which is made with a mix of up to 50% plant-based renewable and recycled PET, will be available nationally in 20-ounce bottles in mid-2020. It will rollout up to 100 additional DASANI PureFill water dispensers, starting in fall 2019. DASANI will also introduce new aluminum cans and new aluminum bottles. The cans will be introduced in the Northeast this fall with both available nationally in 2020. Other initiatives include adding “How2Recycle” labels to all DASANI packages and ongoing “light-weighting” across its product portfolio.[Image Credit: © The Coca-Cola Company]

DASANI’s owner, The Coca-Cola Company, has pledged to make its bottles and cans with an average of 50% recycled material by 2030. In support of this goal, DASANI announced a “robust pipeline” of efforts to lower its plastic footprint. Its HybridBottle, which is made with a mix of up to 50% plant-based renewable and recycled PET, will be available nationally in 20-ounce bottles in mid-2020. It will rollout up to 100 additional DASANI PureFill water dispensers, starting in fall 2019. DASANI will also introduce new aluminum cans and new aluminum bottles. The cans will be introduced in the Northeast this fall with both available nationally in 2020. Other initiatives include adding “How2Recycle” labels to all DASANI packages and ongoing “light-weighting” across its product portfolio.[Image Credit: © The Coca-Cola Company]

CORPORATE ACTION: McDonald’s

The Better McDonald’s Berlin Store Gives The Company Food For Thought

In June this year, McDonald’s opened a concept store for 10 days in Berlin aimed at exploring plastic-free options, eliciting customer feedback and starting debate. The Better McDonald’s Store offered paper straws and wooden cutlery, and edible waffle cups for condiments, wrapped sandwiches in grass-based packaging, and presented Chicken McNuggets in paper bags instead of cardboard boxes. The company said that the response was “very positive”, the grass wrapper was a “hit in terms of eco-friendliness and ease of use”, and the waffle cups were seen as a good way of replacing condiment sachets and containers. Customers were happy with the eco-friendliness of the paper straws, but less so about their ease of use and durability, and believed they wouldn’t miss lids on containers. The wooden cutlery experiment wasn’t a hit.

In June this year, McDonald’s opened a concept store for 10 days in Berlin aimed at exploring plastic-free options, eliciting customer feedback and starting debate. The Better McDonald’s Store offered paper straws and wooden cutlery, and edible waffle cups for condiments, wrapped sandwiches in grass-based packaging, and presented Chicken McNuggets in paper bags instead of cardboard boxes. The company said that the response was “very positive”, the grass wrapper was a “hit in terms of eco-friendliness and ease of use”, and the waffle cups were seen as a good way of replacing condiment sachets and containers. Customers were happy with the eco-friendliness of the paper straws, but less so about their ease of use and durability, and believed they wouldn’t miss lids on containers. The wooden cutlery experiment wasn’t a hit. McDonald’s also said that it is working on other options in its normal restaurants. In Germany, in-house hot drinks are served in porcelain or glass mugs, and McCafé locations in Germany invite customers to bring their own cups in exchange for a 10 cent discount. Selected restaurants in Germany are running a 1 euro deposit system (ReCup) for reusable carry out cups. In the UK, McDonald’s will no longer sell McFlurry products with plastic lids and it is removing single-use plastic from salads, using 100% renewable and recyclable cardboard containers instead. In Canada, the restaurants are using smaller napkins, made from 100% recycled fiber, and switching McWrap® cartons to McWrap wraps. [Image Credit: © McDonald's Corporation]

CORPORATE ACTION: Nestlé

New Institute of Packaging To Lead Nestlé’s Drive To Address Plastic Waste

Nestlé has formally inaugurated a new unit, the Institute of Packaging Sciences based in Lausanne, Switzerland, to double down on the development of new environmentally-friendly packaging solutions that address plastic waste. It will have a science and technology focus on a number of packaging areas, such as refillable and reusable options, simplified materials, recycled materials, and materials that are plant-based, compostable or biodegradable. The move was welcomed by Sander Defruyt, the New Plastics Economy Lead at the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. The new unit also reaffirms Nestlé’s commitment to reinforcing the Swiss innovation ecosystem.[Image Credit: © Nestle]

CORPORATE ACTION: PepsiCo

Coke and Pepsi To Leave Plastics Industry Association

PepsiCo and Coca-Cola have told Greenpeace USA of their decision to withdraw from the Plastics Industry Association. Greenpeace highlights the dichotomy of pledging to end plastic pollution at the same time as supporting bodies that lobby for continued reliance on single-use plastic. Greenpeace says that The Plastics Industry Association uses the American Progressive Bag Alliance (APBA) as a front to advocate against plastic bans in the US. Greenpeace says 15 states have to date passed “pro-pollution preemption laws”. [Image Credit: © Darko Djurin from Pixabay]

PepsiCo and Coca-Cola have told Greenpeace USA of their decision to withdraw from the Plastics Industry Association. Greenpeace highlights the dichotomy of pledging to end plastic pollution at the same time as supporting bodies that lobby for continued reliance on single-use plastic. Greenpeace says that The Plastics Industry Association uses the American Progressive Bag Alliance (APBA) as a front to advocate against plastic bans in the US. Greenpeace says 15 states have to date passed “pro-pollution preemption laws”. [Image Credit: © Darko Djurin from Pixabay]

CORPORATE ACTION: Reckitt Benckiser

RB Pushes Gray As Greener

This summer RB is launching a tub for its Finish Quantum Ultimate that is made from 30% recycled polypropylene (rPP) content. Unlike PET, which has a well-established recycling infrastructure and which can be recycled in light colors that are close to virgin PET, rPP is the ‘ugly duckling’ of plastic recycling. rPP comes from a wide range of polypropylene uses – bottle caps, ketchup bottles, yogurt pots… – is difficult to process and comes out gray. Veolia worked with RB to develop rPP to several strict technical criteria. Instead of using masking pigments or additives, RB says it wishes to make a statement and is using this color as a point of difference and saying it is “proudly grey.” It claims to be the first FMCG company using rPP at scale. This move is part of RB’s commitment to make 100% of its packaging recyclable and for it to contain at least 25% recycled content by 2025.[Image Credit: © Reckitt Benckiser Group plc]

This summer RB is launching a tub for its Finish Quantum Ultimate that is made from 30% recycled polypropylene (rPP) content. Unlike PET, which has a well-established recycling infrastructure and which can be recycled in light colors that are close to virgin PET, rPP is the ‘ugly duckling’ of plastic recycling. rPP comes from a wide range of polypropylene uses – bottle caps, ketchup bottles, yogurt pots… – is difficult to process and comes out gray. Veolia worked with RB to develop rPP to several strict technical criteria. Instead of using masking pigments or additives, RB says it wishes to make a statement and is using this color as a point of difference and saying it is “proudly grey.” It claims to be the first FMCG company using rPP at scale. This move is part of RB’s commitment to make 100% of its packaging recyclable and for it to contain at least 25% recycled content by 2025.[Image Credit: © Reckitt Benckiser Group plc]

CORPORATE ACTION: Unilever

Unilever Japan To Use Recycled Plastic For New Products

Unilever Japan announced that, for new products, instead of using virgin PET it will start using 95% recycled plastic packaging in the second half of 2019 and 100% recycled plastic by the end of 2020. It will start with new products from three brands Lux, Dove and Clear. The move is part of the company’s focus on LBN-P (Less / Better / No-Plastic) as a way “deplasticize,” and part of the company’s broader goal to make 100% of its plastic packaging reusable, recyclable or compostable by 2025, and to ensure at least 25% of plastic used comes from recycled sources. Unilever said the effort excludes plastic that is currently technically difficult to convert due to additives such as colorants.[Image Credit: © Unilever]

Unilever Japan announced that, for new products, instead of using virgin PET it will start using 95% recycled plastic packaging in the second half of 2019 and 100% recycled plastic by the end of 2020. It will start with new products from three brands Lux, Dove and Clear. The move is part of the company’s focus on LBN-P (Less / Better / No-Plastic) as a way “deplasticize,” and part of the company’s broader goal to make 100% of its plastic packaging reusable, recyclable or compostable by 2025, and to ensure at least 25% of plastic used comes from recycled sources. Unilever said the effort excludes plastic that is currently technically difficult to convert due to additives such as colorants.[Image Credit: © Unilever]

Unilever Brand FAB Launches Its First 100% Recycled Plastic Bottle In Colombia

The company will permanently migrate all packaging for its FAB laundry brand’s liquid detergent portfolio in Colombia to 100% PCR plastic, reducing need for virgin plastic by over 78 tonnes per year. This move is one of the first high-density polyethylene (HDPE) 100% PCR bottles for brands that sit under its global Dirt is Good theme. Because the recycling industry in Colombia is weak, with limited infrastructure, Unilever worked with specialist recycling company Biocirculo, which centrally sorts waste plastic collected by over 80 recyclers in Bogotá, ensuring sufficient PCR plastic. FAB will also run ads on TV, online and in-store to raise consumer awareness about sorting waste, and especially plastic, at home.

The company will permanently migrate all packaging for its FAB laundry brand’s liquid detergent portfolio in Colombia to 100% PCR plastic, reducing need for virgin plastic by over 78 tonnes per year. This move is one of the first high-density polyethylene (HDPE) 100% PCR bottles for brands that sit under its global Dirt is Good theme. Because the recycling industry in Colombia is weak, with limited infrastructure, Unilever worked with specialist recycling company Biocirculo, which centrally sorts waste plastic collected by over 80 recyclers in Bogotá, ensuring sufficient PCR plastic. FAB will also run ads on TV, online and in-store to raise consumer awareness about sorting waste, and especially plastic, at home.[Image Credit: © Unilever]

CPGs And Retailers Push To Promote Recycling And Educate Consumers

A couple of examples show how CPGs are seeking to educate consumers to boost recycling.

A couple of examples show how CPGs are seeking to educate consumers to boost recycling. Unilever and Walmart launched Bring It to the Bin, a campaign designed to engage consumers and encourage them to recycle. Bring It to the Bin features Hillary Duff in a series of short videos on social media that offer tips on how to recycle throughout the home.

The campaign includes a number of Unilever’s top brands – Dove, Hellmann's, Seventh Generation and Love Beauty and Planet – with each brand making a commitment to using post-consumer recycled plastic along with How2Recycle labels. The company says these commitments help build to Unilever North America’s aim of having 50% of plastic made of recycled content by the end of 2019 and 100% of plastic packaging being recyclable, reusable or compostable by 2025.

In similar vein, PepsiCo Recycling announced it is working with Diary of a Wimpy Kid author, Jeff Kinney, in a "Be Awesome! Recycle!" campaign. The effort is targeted at school-aged children and will feature Rowley Jefferson, a character in the Wimpy Kid books.

The campaign will support PepsiCo's Recycle Rally program that provides K-12 schools with an array of recycling resources and incentives. PepsiCo says promoting recycling at schools will help improve recycling in America, where 25% of all recycling is contaminated and where 62% of people say a lack of knowledges causes them to recycle incorrectly.[Image Credit: © Unilever USA]

Unilever Partners With Kenyan Plastics Recycling Business

Kenya-based plastics recycling business, Mr. Green Africa, announced that Dutch investor DOB Equity and Global Innovation Fund had invested in the business. Funds will enable Mr. Green Africa to expand its operation and boost processing capacity. Mr. Green Africa aims to build a "fair-trade" industry where waste collectors are fairly compensated. It gathers plastic and processes ready for purchase.

Kenya-based plastics recycling business, Mr. Green Africa, announced that Dutch investor DOB Equity and Global Innovation Fund had invested in the business. Funds will enable Mr. Green Africa to expand its operation and boost processing capacity. Mr. Green Africa aims to build a "fair-trade" industry where waste collectors are fairly compensated. It gathers plastic and processes ready for purchase. Global Innovation Fund invested “in partnership” with Unilever. Just-food.com states that Unilever has invested in the recycling business but it seems more likely that the CPG company has agreed to purchase rPET from it, providing a level of financial security to the co-investors.

A previous press release from Unilever shows that it has a relationship with Mr. Green Africa and worked with 140 primary schools to boost plastics recycling.

The move illustrates the role CPGs can play in upgrading recycling infrastructure. By providing contracts for rPET and other plastics, CPGs can build the market to ensure they have supplies sufficient to meet their various sustainability targets.

[Image Credit: © Mr. Green Africa]

CORPORATE ACTION: Other

UK Government Backs c – Edible, Plastic-Free Drink Packaging

Oohos – containers for drinks up to 100ml – are made entirely from Notpla, a seaweed extract that fully biodegrades in four to six weeks. Ooho manufacturer, also called Notpla, received funding from the UK Government to bring the innovation closer to commercialization, with a broader aim of developing a vending machine for use in gyms or restaurants. It envisions the machine could dispense up to 3,000 Oohos a day, with consumers selecting the drink. Notpla is working closely with Lucozade Ribena Suntory. It sampled 36,000 Lucozade Sport Oohos at the 2019 Virgin Media London Marathon and LRS is working to include Lucozade Sports as an option for the Ooho drink dispenser.[Image Credit: © Notpla Limited]

Oohos – containers for drinks up to 100ml – are made entirely from Notpla, a seaweed extract that fully biodegrades in four to six weeks. Ooho manufacturer, also called Notpla, received funding from the UK Government to bring the innovation closer to commercialization, with a broader aim of developing a vending machine for use in gyms or restaurants. It envisions the machine could dispense up to 3,000 Oohos a day, with consumers selecting the drink. Notpla is working closely with Lucozade Ribena Suntory. It sampled 36,000 Lucozade Sport Oohos at the 2019 Virgin Media London Marathon and LRS is working to include Lucozade Sports as an option for the Ooho drink dispenser.[Image Credit: © Notpla Limited]

Consumers Are At The Heart Of Plastic Reduction Efforts, But Retailers Are Responding

According to Euromonitor, nearly two-thirds (63%) of containers for food, drinks, home, beauty and pet food are plastic, because of its durability, versatility and other characteristics. Recycling or reuse rates, however, are not high enough, partly because of consumer confusion over what can be recycled, perpetuated by a lack of standardization in packaging. Few countries have the recycling infrastructure and rates of Germany, which runs deposit schemes for plastic bottles, but the effort to increase rates is also hampered by consumers being used to disposing of items. Change is afoot. Consumers are more alive to plastic waste issues. Surveys suggest they are more willing today than two years ago to pay more for options that are better for the environment. Retailers like IKEA and UK-based Iceland are reacting to this change. IKEA is stopping the use of oil-based plastics, pledging to manufacture 100% of its products from recycled materials from August next year. It is also ending the use of single-use plastic products from stores and restaurants. Iceland has announced removal of plastic containers from private label products by 2023, using paper trays rather than plastic. [Image Credit: © mohamed Hassan from Pixabay]

According to Euromonitor, nearly two-thirds (63%) of containers for food, drinks, home, beauty and pet food are plastic, because of its durability, versatility and other characteristics. Recycling or reuse rates, however, are not high enough, partly because of consumer confusion over what can be recycled, perpetuated by a lack of standardization in packaging. Few countries have the recycling infrastructure and rates of Germany, which runs deposit schemes for plastic bottles, but the effort to increase rates is also hampered by consumers being used to disposing of items. Change is afoot. Consumers are more alive to plastic waste issues. Surveys suggest they are more willing today than two years ago to pay more for options that are better for the environment. Retailers like IKEA and UK-based Iceland are reacting to this change. IKEA is stopping the use of oil-based plastics, pledging to manufacture 100% of its products from recycled materials from August next year. It is also ending the use of single-use plastic products from stores and restaurants. Iceland has announced removal of plastic containers from private label products by 2023, using paper trays rather than plastic. [Image Credit: © mohamed Hassan from Pixabay]

Drinks Companies In India Cooperate To Limit Scope Of Government Ban On Single-Use Plastic

The Indian government is looking at imposing a ban on single-use plastic from 2022, and drinks companies are seeking clarity on how this will impact their use of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles. The country’s largest packaged water company, Bisleri International, uses only PET bottles. For Coca-Cola and PepsiCo, PET bottles comprise around half of annual sales of their fast-moving pack sizes. The industry claims that PET isn’t single-use plastic because it’s recyclable and it’s uniting to lobby government, arguing that a switch to glass or aluminum cans is not feasible on cost grounds. Elsewhere in India, companies in the travel and hospitality sectors have been reducing single-use. The Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) estimates the country produces almost 26,000 tonnes of plastic annually.[Image Credit: © Willfried Wende from Pixabay]

The Indian government is looking at imposing a ban on single-use plastic from 2022, and drinks companies are seeking clarity on how this will impact their use of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles. The country’s largest packaged water company, Bisleri International, uses only PET bottles. For Coca-Cola and PepsiCo, PET bottles comprise around half of annual sales of their fast-moving pack sizes. The industry claims that PET isn’t single-use plastic because it’s recyclable and it’s uniting to lobby government, arguing that a switch to glass or aluminum cans is not feasible on cost grounds. Elsewhere in India, companies in the travel and hospitality sectors have been reducing single-use. The Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) estimates the country produces almost 26,000 tonnes of plastic annually.[Image Credit: © Willfried Wende from Pixabay]

Sustainable Skincare Brand Maiiro To Put Spotlight on Greenwashing Brands

UK-based sustainable skincare brand Maiiro has launched a new campaign that takes aim at what it sees as greenwashing by many of its competitors. Its aim is to put pressure on those brands to step up their plastic reduction programs, and to encourage consumers to be more aware of the impact of their purchases. The campaign, which Maiiro calls ‘Pack of Lies’, aims to be an information hub on the way in which brands are greenwashing. It will also give tips on how consumers can better recycle plastic. Maiiro has launched as petition too, to push for legislation to improve transparency in brands’ plastic reduction efforts. [Image Credit: © Maiiro]

UK-based sustainable skincare brand Maiiro has launched a new campaign that takes aim at what it sees as greenwashing by many of its competitors. Its aim is to put pressure on those brands to step up their plastic reduction programs, and to encourage consumers to be more aware of the impact of their purchases. The campaign, which Maiiro calls ‘Pack of Lies’, aims to be an information hub on the way in which brands are greenwashing. It will also give tips on how consumers can better recycle plastic. Maiiro has launched as petition too, to push for legislation to improve transparency in brands’ plastic reduction efforts. [Image Credit: © Maiiro]

Earlybirds To Sell Its Snacking Drinks In 100% Plant-Based Packaging

Copyright 2026 Business360, Inc.